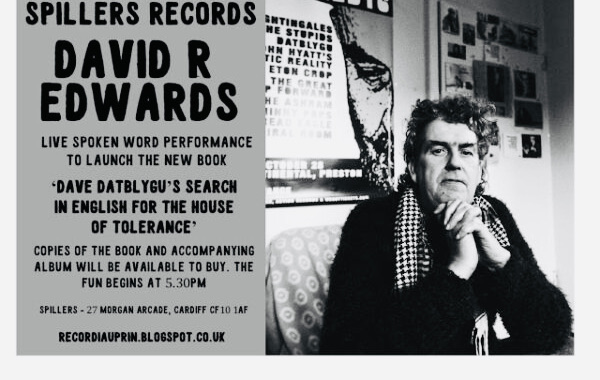

“Does dim rhyfel nawr – ma’r drws ar agor tan y wawr” Er Cof am David R. Edwards

Yn ddiochgar ofnadwy i Sioned Rowlands ac O’r Pedwar Gwynt wnath roi sbardun i sgwennu yn y man cynta;

Thanks to Sioned Rowlands and O’r Pedwar Gwynt who asked (original in Welsh https://pedwargwynt.cymru - subscription)

It is no secret that Datblygu first found their followers outside of Wales. As a teenager I attended gigs in remote country hotels where many of the Welsh speaking audience did not “get” Datblygu. The adulation of Dave in Wales has been very much a belated affair. I am certain David R . Edwards would curl his lips with bemusement at any overt hagiography.

Unlike many writing eulogies for David R. Edwards, I never met “Dave” Datblygu. In my mind he always retained the formal R. of his middle name, resonating with The Fall’s Mark “E.” Smith. But I will try and be familiar here. The music he created with Pat Morgan and T. Wyn Davies has literally travelled with me. From West Wales to Stirling, Brighton, Berkeley, Dublin and now Kells, the cassettes and albums have always been carefully packed ready for their next home. I remain a Datblygu evangelist. Dave’s mordant and black humoured lyrics taught me to love my first language. “Here listen to this” I urge my friends ” this is a Welsh language genius”.

I first encountered Dave’s lyrics as an insert in the compilation ep Dyma’r Rysait which was An Artists For Animals Compilation. The profits of this record were used to produce Welsh animal rights literature. Half of my family were dairy farmers and as a vegetarian, anti-vivisectionist, anti-foxhunting teenager, I could sometimes feel a little out on a limb. The iconoclastic nature of the lyrics was immediately clear to my sixteen-year-old self. Datblygu’s vignette on this EP “Brechdanau Tywod”, detailed a schoolteacher’s boast about eating snails and frogs in Brittany. Slaughterhouses feature in many Datblygu lyrics. I learnt recently that Dave was a betting man. However, in his song “Ugain i Un” he identifies with a broken limbed racehourse:

Oh, oh, oh ie ras ceffylau O’n i’n ugain i un

Des i allan o’r pellter

Ac ennill e ar y Llun.

Ond yn fy ras nesa’

Aeth fy nerth i’r llawr Daeth milfeddyg a gwenu ac yna rhoi fi lawr

I came to Datblygu well before reading Caradoc Evans’s My People – but often wondered if Dave and Caradoc were related. Evans’s acidic depiction of the “Cymry parchus” in West Wales would surely have resonated with Dave’s forensic detail of the everyday. His lyrics operate as vignettes or absurdist short stories. Dave took us with him- from the cattle markets of local discos (“Ms Bara Lawr”), to driving in a long tailback to recycle whiskey bottles while listening to experimental jazz on Radio 3 (“Nofel o’r Hofel”), we were also with him listening to a drunken actor talking about his latest film (“Mynd”). Dave, like Evans, is at his best when focussed on the grotesque, but he is never patronising he is always empathetic. Datblygu is on the side of the underdog, the exploited, the tired, the preyed upon. If anything, it is almost that there is an excess of feeling in Dave’s lyrics. That excess is curtailed by irony. He feels so deeply for his subjects. When Wyau (1988) came out IVF was becoming more commonplace, and stories abounded in the press about multiple births. “Saith Arch Bach” chronicles how science’s petri dish shows little concern for human loss. Dave reminds us how the promises of science offer hope but airbrush the impact of failing pregnancies and neonatal deaths– “saith genedigaeth a methiant gwyddoniaeth.”

Crucially Dave’s lyrics linked Welsh idiom to creativity, not atrophy. Welsh dialect became a resource for wry word play. Dave refuted any sense of right or “proper” Welsh. For him the language was a vivid playground full of errors and aberrations- not to be belittled as “bratiaith” (or second-rate Welsh). This was liberatory to me as somebody who had grown up in an anglophone town in West Wales and frequently felt that my language was under par. My mutations were constantly wrong my “hwn” and “hon” “dau” and “dwy” out of synch. Datblygu were ambassadors for the language- showing how musical experimentation, Welsh’s sonic malleability coupled with Dave’s own acerbic wit, synthesised into something remarkable and accessible. To pinch a phrase from Tradodiad Ofnus Dave sanctioned a “trwydded I camdreiglo.” That the love of language was not always about being right in language. Also, being proud of being Welsh for Dave did not mean one could not address cultural and political failings. When Theatr Bara Caws produced a play about disenfranchised youth and unemployment in 1980s Wales – Paent yn Sychu unsurprisingly the title was a citation from Datblygu’s “Gwlad ar fy Nghefn” The song also became the drama’s soundtrack.

I have followed Datblygu reverentially through their albums Wyau, Pyst, Libertino, Porwr Trallod, more recently Cwm Gwagle. But it is important to reflect on the collaborative impetus to Dave’s compositions. Working with Tŷ Gwydr and Llwybyr Llaethog in the 1990s his aphoristic lyrics and pointed social critiques became wedded with ambient, dub and dance music. Libertino (1993) as an album also mirrored the dance and rave culture of the nineties, but on its own terms. The combination of layered sound, samples and inventive lyrics took Datblygu fans to the dancefloor. David R. Edwards became an adored MC. With the anthemic “Can i Gymru” and “Maes E“ Dave and Datblygu made it big. Subsequent ill health meant he had to retreat for a while.

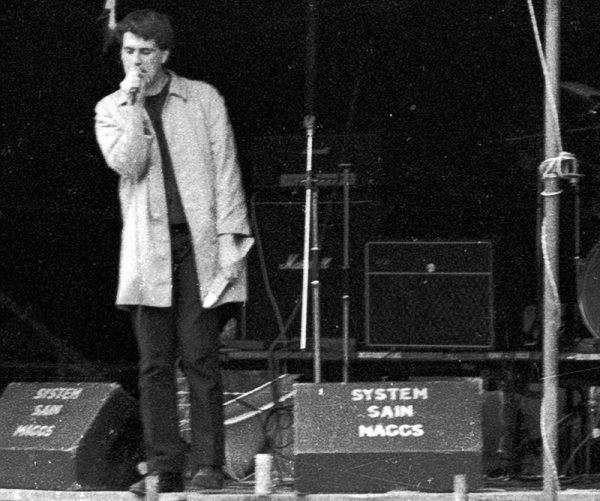

Whenever I hear “Kristion yn y Kibbutz” I will be transported back to Dec 1987. HTV are experimenting with a Welsh language version of The Tube, a short-lived but well intentioned programme called StÎd. Schoolkids have been bussed up from Carmarthen. There has been hours of thought put into what to wear. I have spent several evenings customising a faux suede coat by hand, tapping the needle against a table, making my fingers bleed. It goes well with my mini kilt and silk headscarf I rationalise. The television studio is full of post-industrial objects, oilcans, metal grids – a set evoking the ruins of Thatcher’s Britain. I catch a look of incredulity on the floor manager’s face as a synth starts playing discordantly. The cameramen look nervous. Dave ignores the audience of kids mooching around, he concentrates on his lyrics, Pat strums the guitar and T. Wyn Davies makes the keyboard keen. Pure bliss.

Eventually Wales caught up with Datblygu. Wales recognised them as avant garde trailblazers. We might know David R Edwards now as a prophetic shaman with a wicked sense of humour. He saw Welsh “parch” or culture of conservatism for what it is. This week I was moved to see a retweet in of a post by Dafydd Iwan stating he would always treasure a letter Dave sent him. Datblygu’s early song “Dafydd Iwan yn y Glaw” makes us think about how oppositional and revolutionary figures becoming reified over time. When I first heard the song I thought of it as a put down to the establishment. Now I hear his compassion towards Iwan as a folk hero and the expectations placed upon him by his audience:

Ac mae’n eistedd ar lwyfan Plaid Cymru mae’r glaw yn cwympo drwy y to/

Nid oes ganddo ymbarel

O blydi hell.

Last year I burst out laughing while listening to Dave and Pat discussing their last album Cwm Gwagle on Dewi Llwyd’s Sunday radio programme. With gravitas and tongue in cheek humour, Dave stated that his life’s ambition had been realised: to be on BBC Radio Cymru interviewed by Llwyd.

Even when placed in the public gaze, Dave Datblygu always reframed his relationship to the Welsh establishment. Gyda chydymdeimlad didwyll i Pat a Wyn.

You Tube clip – StÎd. HTV Datblygu (1987)